I first used open-ended polling in a class in 2016. It did not go well.

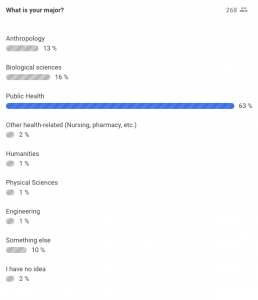

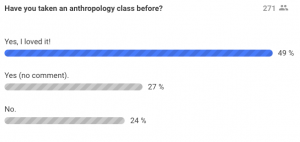

Having seen Bonni Stachowiak use sli.do to great effect in a conference presentation, I decided to incorporate polling into the first day of my 300-student Medical Anthropology course. Sli.do is free and easy to use for anyone with an internet-connected device. I created an event for our class and then asked students to take out their phones or tablets (or partner with a neighbor) and respond to two questions: What is your major? Have you taken an anthropology class before?

The responses were illuminating. I, and the students, discovered that nearly 2/3 of the enrolled students were majoring in Public Health, and over 80% of the students were studying either Public Health, Biological Sciences, or another health-related field. About 1/4 of the students were in their first anthropology class.

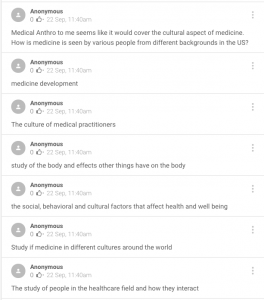

Using the open-ended question feature, I next asked students to share what comes to mind when they hear “medical anthropology.” My intent was to build on students’ assumptions in order to introduce the central concerns of the field and to discuss how the class would intersect with and expand on knowledge they had gained in other (especially health-related) majors.

It started out well enough:

But as I was speaking, I didn’t notice that the background conversation was quickly veering off course:

“This is like a hyper-localized YikYak,” one student said. Amid much laughter, I shut down the poll, tried to recover my composure, and continued the class. I didn’t use polling again that quarter.

I tried again in my 250-student Race, Gender, and Science course the next quarter. This time, I used Poll Everywhere and required students to register for an account. (I paid the instructor fee so registration was free for students.) Students’ names were not publicly associated with their responses, giving anonymity among students. But if any concerns arose, I could access individual responses through the software.

I again collected information about majors and previous experience in anthropology courses, but this time I experimented with polling to achieve several other goals.

Identify prior knowledge/assumptions:

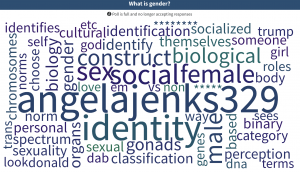

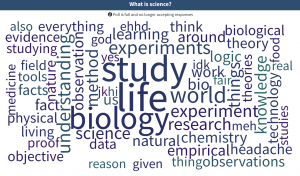

During our second class, I asked students, What is race? What is gender? What is science?, and displayed their responses as word clouds.

We had some technical difficulties at first. Responses to “What is race?” weren’t recorded, and the dominant response to “What is gender?” was “angelajenks329,” the code students needed to use to submit their responses. I also discovered that several of the words associated with “gender” were considered profanity and automatically replaced with *******. I adjusted settings, clarified submission processes with students, and by the time we got to “What is science?,” we’d mostly figured out how to use the system.

The resulting word clouds allowed me to quickly identify some of the knowledge and assumptions about course topics that students entered with, and they offered a framework I could use to discuss the central goals and perspectives of the course.

Introduce new topics and connect course discussions to contemporary issues:

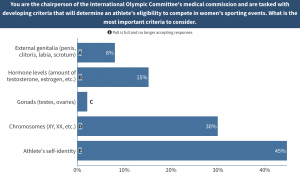

I also used polling to introduce specific topics. The following poll, for example, used a contemporary, “real world” question to challenge binary sex distinctions and to highlight some of the ways both sex and gender categories are socially produced. Following this poll, we discussed the problems with using any single biological feature to designate gender, and the rest of the class session focused on intersexuality, non-binary gender identities, and the social processes through which notions of normality are produced and enforced.

Review and retrieval practice:

I often began class sessions with quick (ungraded) quizzes that reviewed terms or concepts from previous classes. These quizzes gave students an opportunity to practice retrieving information from their memories and allowed me to identify and clarify points of confusion. For example, the following question asks about research that led to the approval of the drug BiDil for the treatment of heart disease in African Americans. The correct answer is “False.”

Respond to questions:

One of my favorite features in Poll Everywhere is that respondents can view and “upvote” each others’ (anonymized) responses to open-ended polls. I used this feature to solicit questions at the end of a lesson or before exams. I can’t sort through several hundred responses during class, but this allowed me to quickly identify the top questions and respond to them immediately.

Gather feedback and encourage students to reflect on their learning:

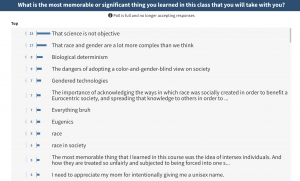

Finally, I used the up-vote feature again at the end of the course, asking students to identify the most memorable or significant thing they’d learned and would take with them. This question encouraged students to reflect on their learning throughout the course and provided me with important feedback about the topics and arguments that most resonate with students. I have used this information as I revise the course to teach again.

I’m preparing to teach my large Medical Anthropology course again this fall, and I’d love to hear about other ways instructors are using polling in their classes!