About

Jennifer Thompson Canino was a 21-year-old university student when a man broke into her apartment and sexually assaulted her. Unable to physically fight back, she chronicled every part of this man determined to remember every detail.

Based on her eyewitness testimony, Ronald Cotton was sentenced to life in prison.

The problem was, he was innocent.

Jennifer is white, and Ronald is black.

According to the Innocence project, mistakes in eyewitness testimony contribute to over 70% of wrongful convictions overturned by DNA evidence. Of these exonerations, 40% were the result of cross-race identifications [1]. These statistics highlight some of the deleterious consequences of the ‘Other-Race Effect,’ a phenomenon where we are worse at remembering the faces of individuals of other races. But how much worse?

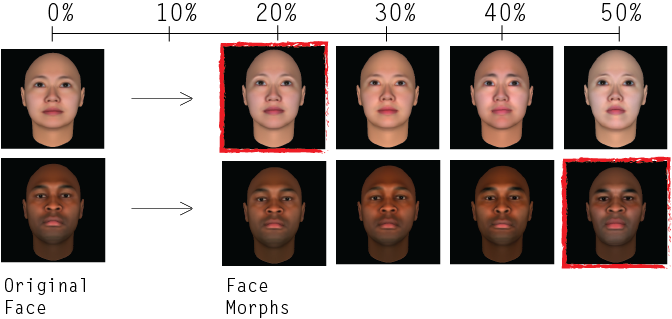

Jessica Yaros, a graduate student in the Translational Neuroscience Laboratory, designed a computer game to test people’s ability to remember the faces of individuals of other races. Subjects were asked to tell the difference between faces they’ve previously memorized, and new faces that have been morphed on a scale of 20 to 50%. This allows researchers to discover how different one face needs to be from another for a participant to distinguish between the two.

Yaros found that Asian participants had an incredible ability to detect even the smallest changes between faces of their own race in the 20% morphs. But they could hardly tell other-race faces apart until they were maximally deviated 50% from one another. [2]

To understand what is happening in the brain of these subjects, Yaros placed the participants in an MRI scanner while they played the game. While the data from this study is still being analyzed and it is too early to share specific findings, Yaros reports seeing widespread differences in brain activity of participants during viewing and recall of the same- and other-race faces. The results of this study will give researchers a better understanding for how the Other-Race Effect is supported by differences in neural activity.

Let’s remember where we started. Ronald Cotton spent ten years in prison for another man’s crime. After his exoneration by DNA evidence, he forgave Jennifer, they wrote a book together and traveled the country advocating for eye-witness policy reform.

But despite their work, most wrongfully convicted people will not be so lucky. In the future, science can help the criminal justice system by continuing to expand on research underlying deficits in other-race face memory and working with policy makers to implement empirically informed changes to mitigate the negative consequences of over-relying on eyewitness testimony or cross-race identifications.

References

1. Cross-Racial Identifications: Solutions to the “They All Look Alike” Effect

Impact

Social psychologists have made important strides on the topic of mechanisms likely contributing to the Other-Race Effect. Birders, car buffs, and radiologists become experts in the categories they focus on because visual recognition can be tuned to excel with identification of objects we see often. In the same way, humans are often better at recognizing differences in the faces with which we are most familiar. But research has also shown that we pay more attention to faces of our own group, further exacerbating differences in face recognition ability. Research like ours can importantly lend physiological evidence to support these theories—which overall have been based on behavioral rather than neuroimaging findings.

While disparities in cross-race identifications and fallibility of eye-witness testimony has been studied for decades, reforms within the criminal-justice system have been slow. Fortunately, in recent years there has been some increased willingness towards making data-driven policy decisions – attributable in part to a landmark publication from the National Academies in 2014. The report, ‘Identifying the Culprit: Assessing Eyewitness Identifications’ lays out how scientific findings on human vision and memory can be used to improve eye-witness testimony. Within 5 years of its publication, 19 states had implemented changes recommended by the report.

While much more needs to be done, the continuing impact of this report highlights the importance of neuroscientific and psychological research on memory and vision deficits and disparities, especially with applications to criminal-justice where the stakes are so high.

Future Studies

- What kind of strategies during encoding of other-race race faces can replicate behavior and brain activity more in-line with same-race face recognition?

- Can training paradigms be developed that have long lasting impacts on facial recognition ability?

- How might stress and anxiety during encoding modulate face recognition for members of one’s own and other race groups?

- As time passes, do memories of faces across race degrade at the same rate?

Project Team

Jessica Yaros

Graduate Student